Toxoplasma gondii is an extremely serious parasite that is a leading cause of hospitalizations (fourth leading) and death (second only to Salmonella) from foodborne sources in the United States. There are 300 to 4,000 cases of congenital toxoplasmosis each year in the United States. The illness causes blindness, deafness, mental deficiencies, epilepsy and/or death in babies whose mothers contracted the parasite during pregnancy. T. gondii infects more than 800,000 people each year in the United States. Non-congenital symptoms can include blindness (3,600 per year), and in people who are immunocompromised, the illness can cause encephalitis, dementia, mental illness or death. While healthy adults can recover from the symptoms of toxoplasmosis, the parasite remains in their bodies and can be reactivated when they become immunocompromised. [CDC, 2011; Kotula, et al., 1991; CDC, 2021; FDA, 2018; Dubey, 1994] Approximately 50% of the cases of human toxoplasmosis in the U.S. each year are from food [FDA, 2018].

Toxoplasmosis is a worldwide problem, and the CDC estimates that 40 million people in the United States have T. gondii in their body [CDC, 2018]. Dubey placed the estimate at 30-40% of the adult U.S. population [Dubey, 1994] which is 98 to 131 million people) carry the parasite. Many other countries have higher, and much higher, percentages of infected people [Dubey and Beattie, 1988].

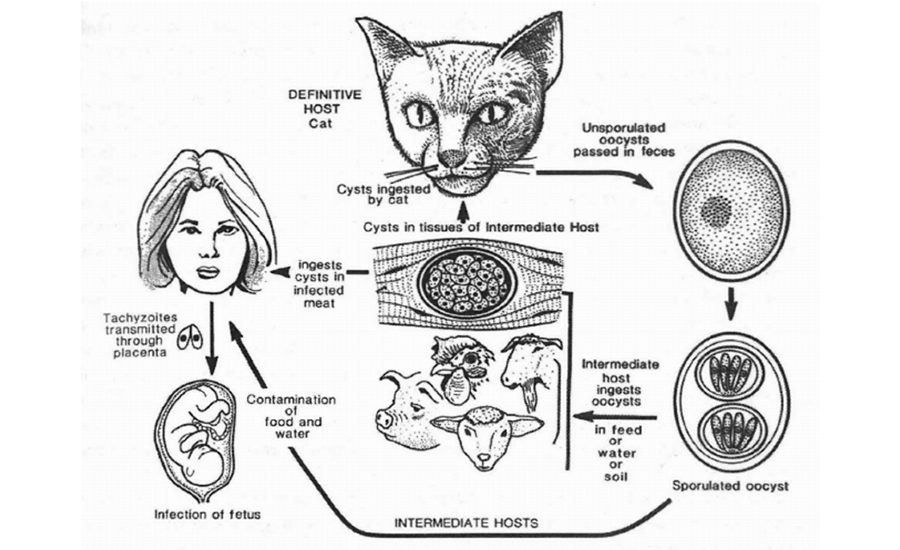

People can be infected with T. gondii, which can be found in meat and poultry, water, soil, on produce (unwashed fruits and vegetables) that have been contaminated by cat feces [Dubey and Beattie, 1988; Dubey, 1994; Montazeri et al., 2020; CDC, 2021]. The animals are infected by eating feed or other things in their environment, that have been contaminated with T. gondii.

One may ask why the meat and poultry industry should be concerned about T. gondii since there are heat (cooking), and cold (freezing) procedures to ensure the parasite is destroyed in meat and poultry. After all, consumers are often given cooking instructions on retail packages of meat and poultry, and the USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) requires a safe handling statement on packages of raw and not fully cooked meat and poultry products [FSIS, 1994]. The answer is partly because eradicating the parasite is the right thing to do. But also, meat is blamed for toxoplasmosis when the source may well have been contaminated water, raw fruits and vegetables, soil, cat litter boxes or anywhere else infected cats may have left their feces.

Preventive measures

Starting in the early 1980s, the Meat Science Research Laboratory of the Agricultural Research Service, USDA investigated the accuracy of the Ransom and Swartz recommendation that meat should be cooked to 137oF [Ransom and Swartz, 1919]. But in 1919, cooking times were longer. More modern cooking methods, such as using microwave and deep-fat frying, decrease the “come up time” which contributed to the thermal destruction of pathogens. The Meat Science Research Laboratory cooked pork infected with Trichinella spiralis in a microwave oven, and the parasite was not destroyed uniformly [Kotula, et al., 1982]. The FSIS requested we determine the thermal death times using heat and cold for T. spiralis so they could provide consumers and the meat industry with accurate data for destroying that parasite. The data were published in the Federal Register, became the FSIS standard and were published in the Code of Federal Regulations [9 CFR 318.10, 1985-2017], and it can now be found in a FSIS Compliance Guideline [2018].

FSIS Division former Director of Pathology and Epidemiology Jack Leighty, D.M.V., realized that Toxoplasma gondii is second to Salmonella in medical concerns, so he requested we provide thermal death times (heat and cold) data for that parasite as we had for T. spiralis. It was observed that T. gondii was destroyed more readily than T. spiralis, so that if one were to test for T. spiralis after heat or cold treatments and found it to be negative, testing for T. gondii would not be necessary.

The Issue

Once infected, T. gondii persists in one’s body. Dr. J.P. Dubey, former leader of the Animal Parasite Diseases Laboratory, ARS, USDA, produced Figure 1, which shows T. gondii cysts from an infected intermediate host such as a mouse, transform inside a feline into unsporulated oocysts. The oocysts are then excreted in cat feces where they can contaminate produce (fruits and vegetables), or water and be consumed by farm animals or humans. The oocysts can survive and be infective to humans or animals in outside weather up to 1 to 1.5 years [Dubey and Beattie, 1988; Dubey, 1994]. Interestingly, it appears that mice infected with T. gondii lose their aversion to cat urine [Ingram et al., 2013] and are less likely to avoid areas inhabited by cats making them easier prey. When a cat eats an infected mouse, the cat becomes infected. Figure 1 also shows that a pregnant woman can pass tachyzoites to her unborn baby.

It is estimated that 35% of domestic cats and 45% of wild felids (feral cats and other wild cat species) in the U.S. have been infected with Toxoplasma gondii [Montazeri et al., 2020]. There are an estimated 93.5 million domestic cats [Wikipedia, Cats in the United States, 2021], 70 million feral cats [Mott, 2004], and 733,000 to 2 million wild cat species, primarily bobcats and cougars in the U.S. [Wikipedia, Bobcat, 2021; Wildlife Informer, 2021]. Therefore, over 64.5 million cats (domestic, feral, and wild) have been infected with T. gondii. Even if cats only transmit T. gondii once in their lives, the numbers above indicate that there is a very large reservoir of felids that may have and can transmit T. gondii.

Research obstruction greatly slowed advancements in understanding T. gondii

In 1987, the Washington Post reported that a group of individuals broke into secure facilities of the USDA’s Animal Parasite Diseases Laboratory in Beltsville, Maryland and took 27 research cats, 11 of which had been infected with Toxoplasma gondii parasites for research experiments. The cats, including the infected cats, were then distributed to families willing to take them. [Dawson, 1987]

In 2019, another group attempting to ‘save’ the life of cats, convinced 75 members of the U.S. Congress to remove all funding from the Animal Parasite Diseases Laboratory so as to stop any further research on T. gondii using cats [H.R.1622, 2019]. (The members of Congress who sponsored and co-sponsored this bill can be found at https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/1622/cosponsors) However, an article entitled, “Scientists decry USDA’s decision to end cat parasite research” — in Science Magazine stated, “But many researchers say the lab’s demise will undermine efforts to fight the devastating parasite, which is the world’s leading infectious cause of blindness and causes roughly 190,000 babies to be born with defects each year. In the United States, which has about 1 million new infections annually, it is the second-leading food-borne killer, causing about 750 deaths.” The lab was also working to develop a vaccine for cats, which would interrupt the parasite’s life cycle, and therefore protect people from infection. Additionally, the laboratory was providing samples to other scientists throughout the world for studies on T. gondii. This parasite is a world-wide problem. [Wadman, 2019] One wonders why Congress would choose a few already well-treated cats over the health and well-being of millions of U.S. citizens.

FSIS mandate

FSIS has a budget of 1.388 billion dollars for 2022 [United States Department of Agriculture FY 2022 Budget Summary, page 81]. It is responsible for ensuring commercial meat, poultry and eggs are safe, and wholesome. It inspects the industries to ensure their procedures comply with regulations, approves labels to provide consumers with information, including cooking procedures, and ensures products are packaged properly. Their vast inspection program is designed to prevent raw and cooked meat, poultry and eggs from causing illness to the consuming public. That is a challenging task.

Cats are the definitive host of the T. gondii parasite. Ordinarily, FSIS could request Dr. Dubey’s Laboratory, of the Agricultural Research Service of USDA, to perform the necessary research to protect humans from this parasite, including developing a vaccine against that parasite in cats; however, as we have seen 75 members of the U.S. Congress passed a law to prevent the USDA from using cats in T. gondii or any research. Can Congress disallow FSIS from performing its stated duty to protect consumers? Is Congress really unaware of the serious illness caused by T. gondii?

Solutions:

- Vaccination

- Serological testing of meat animals, and indemnity

- Testing of imported meat

- Industry cooperation

In 1990, Jack Leighty, D.V.M., former director of the Pathology and Epidemiology Division at the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS), published an article suggesting an oral vaccine be produced to prevent cats from being infected with T. gondii [Leighty, 1990].

Other research has investigated vaccines and emphasized that the life stage of the parasite in the host (definitive or intermediate) must be considered to make the proper vaccination for that animal [Dubey, 1996].

A vaccination for cats, the hosts to the parasite, would stop the life cycle of T. gondii and could go a long way to eradicating it. While an injectable vaccination could work with domestic cats who receive regular veterinary care an oral vaccine would be necessary for bait stations to vaccinate feral cats.

It would take an estimated $10 million to develop the vaccine. But once associated costs of facilities and personnel are calculated, the cost would be $1 billion. However, companies and universities that develop vaccinations may be looking for a new project. The meat and poultry industry would be well served by supporting this research. A vaccine company would be well served if they were to support in-house and cooperative research with universities.

Eradicating Toxoplasma gondii in cats with an oral vaccine that can be used with feral as well as household cats is imperative.

FSIS is responsible for providing cooking and freezing guidelines to destroy parasites such as Trichinella spiralis and Toxoplasma gondii in meat potentially containing those parasites. We suggest an indemnity procedure be established. Using serological methods, animals with Trichinella spiralis or Toxoplasma gondii would be identified and would be segregated for use in the fabrication of retail cooked or frozen items. The owner would be paid for the loss of income because of the presence of parasites. The retailer could ask a higher price because the label could include the statement “cooked or frozen to ensure safety.” This procedure adds effort and costs, but it also saves lives.

By identifying animals and herds/flocks with these parasites, management procedures can be put into place to protect future animals and the herds/flocks from infection, thus increasing the safety of the meat and poultry.

The incidence of T. gondii in cats is higher in other parts of the world than in the U.S. [Montazeri et al., 2020], so meat imported into the U.S. needs to be tested for T. gondii. If positive, the meat must be used for products that have been sufficiently cooked or frozen to destroy the organism before the product reaches the consumer. Meat frozen before being imported would need documentation demonstrating the temperatures and times used (initially and/or during transport) were sufficient to kill the parasite.

a) The salting, drying and curing parameters used to inactivate Trichinella spiralis were assumed to work for Toxoplasma gondii but the actual research needed to be done.

It has been determined that T. gondii bradyzoites are inactivated in dry-cured hams, with the salting and curing parameters (including the equalization step and time) being critical for the inactivation. [Fredericks, et al., 2020]

b) The National Pork Board- [project #14-134] funded research projects which described the low-salt conditions necessary to inactive Toxoplasma gondii bradyzoites in dry-cured, ready-to-eat pork sausage.

Importantly, this research described and updated the meat chemistry parameters, including salt level, cure, sugar level, pH and water activity that can be used to predict the effectiveness of a process during sausage formation and curing. [Hill, et al., 2018; Fredericks, et al., 2019]

Advantages to industry

Industry can assist research scientists by providing technical support and receive public recognition and thanks by the authors of the resultant research papers in those papers. The information provided through publication of this research can be used to validate current industry methods or provide new data that can be used by industry to produce safer products.

The time has come to preserve the health of millions of citizens of the United States (and the world) by eradicating Toxoplasma gondii. We have the technology. We just need the funding.

References:

9 CFR 318.10, 1985-2017. Code of Federal Regulations, Title 9, Section 318.10: Prescribed treatment of pork and products containing pork to destroy trichinae. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C.

CDC, 2011. CDC Estimates of Foodborne Illness in the United States, Findings. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.cdc.gov/foodborneburden/2011-foodborne-estimates.html

CDC, 2018. Parasites – Toxoplasmosis (Toxoplasma infection) Page last reviewed: August 29, 2018 https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/toxoplasmosis/index.html

CDC, 2021. Neglected parasitic infections in the United States – Toxoplasmosis. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/resources/pdf/npi_toxoplasmosis.pdf#:~:text=The%20T.%20gondii%20parasite%20infects%20over%20800%2C000%20persons,300%E2%80%934%2C000%20cases%20of%20congenital%20%28mother-to-child%29%20toxoplasmosis%20each%20year

Dawson, V., 1987. Diseased cats taken from USDA lab in MD. The Washington Post, August 25, 1987. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1987/08/25/diseased-cats-taken-from-usda-lab-in-md/fee476aa-747f-40b0-bb6c-c0fbbd60ccdd/

Dubey, J.P. 1994. Toxoplasmosis. J. of the American Medical Association 205: 1593-1598.

Dubey, J.P., 1996. Strategies to reduce transmission of Toxoplasma gondii to animals and humans. Veterinary Parasitology 64 (1996) 65-70.

Dubey, J. P., and C. P. Beattie 1988. Toxoplasmosis of animal and man. Boca Raton, FL. CRC Press Inc. 1-220.

Dubey, J.P., A.W. Kotula, A. Sharar, C.D. Andrews, and D.S. Lindsey, 1990. Effect of high temperature on infectivity of Toxoplasma gondii tissue cysts in pork. Journal of Parasitology 76(2):201-204.

FDA, 2018. Toxoplasma from Food Safety for Moms to Be. https://www.fda.gov/food/people-risk-foodborne-illness/toxoplasma-food-safety-moms-be

Fredericks, J., D.S. Hawkins-Cooper, D.E. Hill, J. Luchansky, A. Porto-Fett, H.R. Gamble, V.M. Fornet, J.F. Urban, R. Holley, J.P. Dubey, 2019. Low salt exposure results in inactivation of Toxoplasma gondii bradyzoites during formulation of dry cured ready-to-eat pork sausage. Food and Waterborne Parasitology 12 (2019), e00047.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2405676618300295?via%3Dihub

Fredericks, J., D.S. Hawkins-Cooper, D.E. Hill, J.B. Luchansky, A.C.S. Porto-Fett, B.A. Shoyer, V.M. Fournet, J.F. Urban, Jr., J.P. Dubey, 2020. Inactivation of Toxoplasma gondii Bradyzoites after Salt Exposure during Preparation of Dry-Cured Hams. Journal of Food Protection, Vol. 83:(6):1038–1042.

FSIS, 1994. Mandatory Safe Handling Statements on Labeling of Raw and Partially Cooked Meat and Poultry Products.

https://www.fsis.usda.gov/sites/default/files/media_file/2021-02/7235.1.pdf

FSIS, 2018. FSIS Compliance Guideline for the Prevention and Control of Trichinella and Other Parasitic Hazards in Pork Products. https://www.fsis.usda.gov/sites/default/files/import/Trichinella-Compliance-Guide-03162016.pdf

H.R.1622 - KITTEN Act of 2019.

https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/1622/text

Hill, D.E., J. Luchansky, A.Porto-Fett, H.R.Gamble, V.M. Fournet, D.S.Hawkins-Cooper, J.F.Urban, A.A.Gajadhar, R.Holley, V.K.Juneja, J.P.Dubey, 2018. Rapid inactivation of Toxoplasma gondii bradyzoites during formulation of dry cured ready-to-eat pork sausage. Food and Waterborne Parasitology 12 (2018), e00029.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2405676617300161?via%3Dihub

Ingram, W.M., L.M. Goodrich, E.A. Robey, and M.B. Eisen, 2013. Mice infected with low-virulence strains of Toxoplasma gondii lose their innate aversion to cat urine, even after extensive parasite clearance. arXiv https://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/1304/1304.0479.pdf

Kotula, A.W., J.P. Dubey, A.K Sharar, C.D. Andrews, S.K. Shen, and D.S. Lindsay, 1991. Effect of freezing on infectivity of Toxoplasma gondii tissue cysts in pork. Journal of Food Protection 54(9):687-690.

Kotula, A.W., K.D. Murrell, L. Acosta-Stein, and I. Tennent, 1982. Influence of rapid cooking methods on the survival of Trichinella spiralis in pork chops from experimentally infected pigs. Journal of Food Science 47(3): 1006-1007.

Leighty, J.C., 1990. Strategies for control of toxoplasmosis. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 196:(2):281-286.

Montazeri, M., T.M. Galeh, M. Moosazadeh, S. Sarvi, S. Dodangeh, J. Javidnia, M. Sharif, and A. Daryani, 2020. The global serological prevalence of Toxoplasma gondii in felids during the last five decades (1967–2017): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Parasites & Vectors 13:82:1-10. https://parasitesandvectors.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13071-020-3954-1

Mott, M. 2004. U.S. faces growing feral cat problem. National Geographic September 7, 2004. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/feral-cat-problem?loggedin=true

Ransom, B.H. and B. Schwartz, 1919. Effects of heat on trichinae. Journal of Agricultural Research 17(5): 201-221. https://naldc.nal.usda.gov/download/IND43966140/PDF

United States Department of Agriculture FY 2022 Budget Summary https://www.usda.gov/sites/default/files/documents/2022-budget-summary.pdf

Wadman, M., 2019. Scientists decry USDA’s decision to end cat parasite research. Science Magazine, April 9, 2019. https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2019/04/scientists-decry-usdas-decision-end-cat-parasite-research

Wikipedia, 2021. Bobcat. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bobcat

Wikipedia, 2021. Cats in the United States. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cats_in_the_United_States

Wildlife Informer, 2021. Mountain Lion Population (In Each U.S. State). https://wildlifeinformer.com/mountain-lion-population/