Antimicrobial spraying plays a key role in the never-ending battle to eradicate pathogens from meat and poultry carcasses.

While many operators, particularly smaller processors, position antimicrobial spraying as a low-cost, efficient, and effective method of reducing bacterial contamination, the procedure also can be hazardous to workers who do not follow the proper safety measures, analysts say.

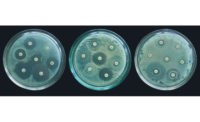

Spraying involves the application of such elements as organic acids (including lactic, acetic, and citric), peroxyacetic acid, and chlorine-based compounds such as sodium hypochlorite on the surface of carcasses, parts, and organs. The activity can result in up to a 99% reduction of bacteria on carcass surfaces while extending the shelf life of meat by several days with a cost of only a few pennies to dimes per carcass, according to the Alberta, Canada-based Alberta Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Rural Economic Development.

“Research studies have shown that applying a pre-chill treatment solution containing 2% lactic acid to beef carcasses reduced the counts of Salmonella typhimurium and E. coli O157:H7 by five log cycles,” says Nicole Keresztes-James, supplier assurance programs technical scheme lead for NSF International, an Ann Arbor, Mich.-based food safety auditing firm and standards developer. “In comparison, when a water-only wash was applied, the result was a reduction of just three log counts.” The greater the logarithm (log) reduction, the more effective a product is at killing bacteria and other pathogens that can cause infections.

To better achieve such results, prior to antimicrobial spraying, operators should clean the carcass surface with warm water and allow excess water to drip from the carcass for at least five minutes to dissipate the water film and enable the antimicrobial to make better surface contact. This information comes from a report from the Department of Food Science at Pennsylvania State University (Penn State), Department of Animal Science and Food Technology at Texas Tech University, and the Department of Food Science and Nutrition at Washington State University. The report is from a study at Penn State on antimicrobial spray treatments for red meat carcasses in very small meat establishments.

Do not rush the process

Such contact is important as harmful bacteria, including Campylobacter spp., may still be present on meat surfaces after washing with warm water, the report shows. “If the carcass is not given adequate time to drip, then the excess water film could dilute the acid and make it less effective,” according to the report.

After five minutes of drip time, operators should rinse the carcass with enough solution so it covers the carcass completely and some antimicrobial fluids drip off. Operators should rinse a side of beef for at least one minute while rinsing other red meat carcasses including lamb, pork, veal, and goat for at least 30 seconds, the report shows.

Spraying equipment options include heavy-duty stainless steel tanks, battery-operated sprayers that can deliver fluid at a constant rate and pressure and can take the form of a backpack or tank on wheels, and garden sprayers that operate with a gentle flow rate and may take longer to thoroughly rinse a carcass. The report notes that many garden sprayers do not have a pressure gauge and require manual pumping to pressurize, though processors can retrofit the sprayer with a gauge, along with a pressure relief valve for safety and a quick-connect plug to allow users to pressurize the tank rapidly.

The effectiveness of antimicrobial sprays, meanwhile, can vary in accordance with the application, Keresztes-James says. “High water temperatures can lead to off-gassing of antimicrobials, and the high organic load may deactivate them,” she says, adding that efficacy also is dependent on the pH of the environment in which spraying occurs, including the chemical composition of the various carcasses and the pH of the water used for solution preparation. Potential hydrogen (pH) is a measure of the acidity of a solution.

Some antimicrobial sprays also require longer residence times on the carcass for maximum effect, Keresztes-James says. “Sprays have been found to be less effective in reducing microorganisms in meat applications where the product has more cut muscle surfaces, such as trim,” she adds. “Microorganisms can find hiding places in cracks and crevices more easily and can elude the spray, reducing its effectiveness.”

Sprays, meanwhile, can cause undesirable colors, textures, and flavors to appear in the meat, depending on the antimicrobial treatment, Keresztes-James says. A “graying” reaction, for instance, may occur when an antimicrobial interacts with the heme in the animal’s blood, she says.

Reduce the worker safety risk

The risk of injury to workers spraying antimicrobials, meanwhile, makes it crucial for processors to implement and enforce safety measures, analysts say. Certain antimicrobial treatments such as peracetic acid, which operators frequently use in poultry processing facilities, can have a corrosive and irritating effect on people’s eyes, mucous membranes of the respiratory tract, and skin, Keresztes-James says.

“Exposure to high concentrations of airborne chemicals can quickly overwhelm workers, with undesirable health outcomes that range from irritation to severe irreversible effects, including death,” she says, noting that spray applications in open areas create more exposure to workers than enclosed environments, such as a cabinet.

To best protect employees, operators should ensure workers are wearing the proper personal protective equipment (PPE), while receiving regular training on the use and hazards of antimicrobial spraying, Keresztes-James notes.

Necessary PPE can include goggles, chemical gloves, face shields, rain suits and sleeves that go over the gloves, says Jen Allen, vice president of operations and engineering for Allen Safety, an Orlando, Fla.-based global safety and process improvement company. Processors should consult manufacturers’ safety data sheets to determine the proper PPE for chemical handlers in accordance with the dilution requirements and application methods, Allen says. It also is important that the safety sheets are easily accessible in emergency situations, the Penn State report notes.

Diluting antimicrobials mechanically to avoid worker contact with the concentrated chemical should be another consideration, Keresztes-James says, adding that it also is important for processors to store chemicals properly in well-ventilated spaces and tightly closed containers.

Keep the chemical under control

Full-strength chemicals can cause additional harm with incidents more likely to occur when there is accidental rupture of the tote or barrel containing the compounds, Allen says. Such occurrences may happen when operators use a forklift to move the chemicals into storage areas and production floors.

Workers also face risks from accidentally spilling chemicals, using chemicals at a higher strength than what manufacturers recommend by not diluting properly and changing or modifying application methods when mixing chemicals, she says.

Mixtures typically present little safety threat to employees when there is proper titration and users follow the recommended dilutions, Allen says. “Locations will want to work closely with chemical company reps to ensure the product is being used as sold or intended, and that handlers are trained on the specific chemical’s hazards, proper use, handling, mixing, storage and the limitations of the chemical,” she says.