“2020 was a below-average year with moments of terror,” says Steve Meyer, Ph.D, an economist with Partners for Production Agriculture, based in Ames, Iowa.

The reason? Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), of course, which reached community spread by the end of February and is rapidly escalating in the last quarter of the year to infect more than 11 million people and kill a quarter million American citizens.

The meat, poultry and pork industries grappled with employee safety, labor shortages, supply-chain slowdowns, product backlogs and inconsistent demand because of shutdowns. But the pandemic also allowed the industry to brainstorm solutions to longstanding challenges, which bodes well for the future as consumers wait for promising vaccines.

“2020 was, of course, an unprecedented year of turmoil and turbulence for meat industries,” says Derrell Peel, Ph.D, livestock marketing specialist at Oklahoma State University’s Cooperative Extension, based in Stillwater. “The pandemic pushed the U.S. and global economies into recession and caused massive upheaval in meat industries.”

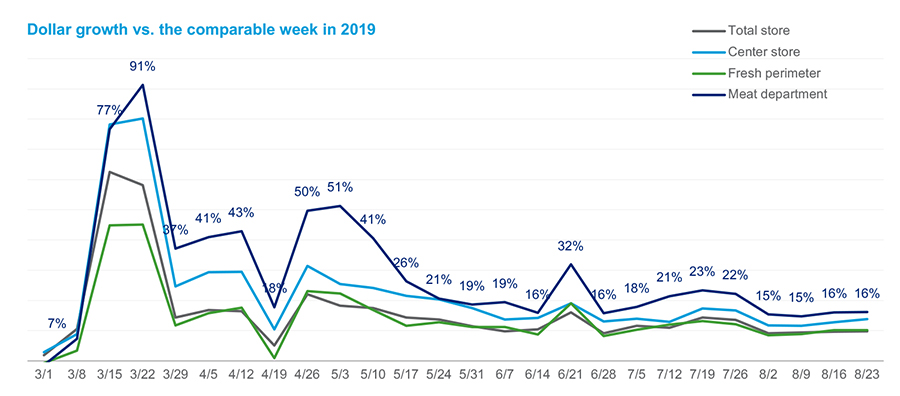

These industries were hit by two overlapping waves of impacts. “The initial shutdown of the economy in March severely reduced foodservice markets and caused an abrupt shift of meat demand onto retail grocery markets,” says Peel. “The specialization of foodservice and retail grocery supply chains meant that there were significant disruptions in product flows with foodservice initially unable, for the most part, to shift to retail grocery supply. This resulted in temporary product shortages in supermarkets aggravated by a surge in consumer demand to stock up home inventories amid the uncertainty.”

By the middle of April, COVID-19 hit packing and processing facility labor forces. This resulted in shutdowns and reduced capacity among many facilities, simultaneously reducing meat production through April and May.

“The resulting product shortages perpetuated the empty supermarket shelves into June and, to a limited extent, continuing until today,” Peel says.

Foodservice meat supply companies were in many cases unable to switch to the type of processing needed for retail and to provide packaging and labeling for retail grocery.

“The impacts on foodservice supply chains continue as the pandemic is not over, and foodservice is still significantly reduced,” Peel says. “Some foodservice sectors, such as QSRs (quick-service restaurants), have recovered significantly and many restaurants have adapted to less dine-in and more take-out and delivery service.”

Cold weather and seasonal changes in demand may bring new challenges to foodservice sectors and the threat of additional pandemic-related effects looms large, says Peel.

*Click the image for greater detail

Adjusting to a new reality

While the economic performance of meat industries in 2020 varies widely across firms and sectors, the foodservice sector clearly took the hardest hit. But all firms struggled with disruptions, variable production and supply and increased costs.

“However, despite the roller coaster path this year, overall meat production did not change much,” Peel says. “Current estimates for beef, pork and broiler production are within 1 percent of estimates made in January. The disruption in packing and processing in April/May did result in some depopulation of pigs that could not be slaughtered and a limited amount of broilers as well.”

Yet subsequent industry adjustment in the poultry side and heavy animal weights for hogs and cattle offset slaughter reductions to maintain annual meat production.

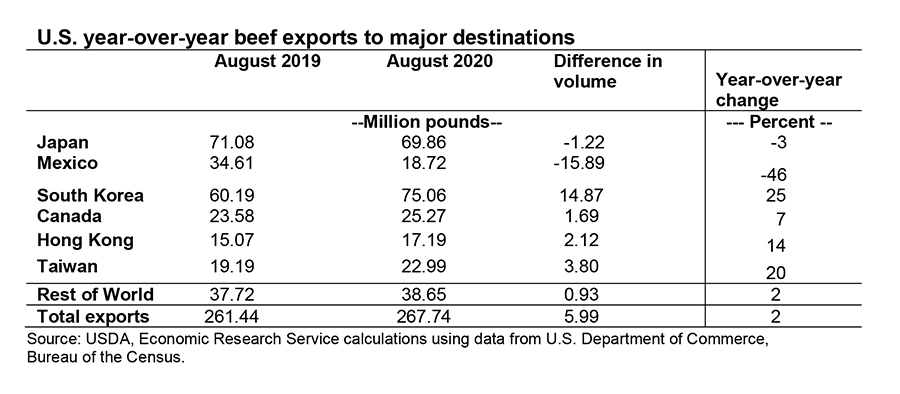

Meat exports were disrupted as well, and the annual export forecast was reduced as a result of the pandemic.

“However, overall meat demand appeared to remain quite strong with less economic impact on demand than was feared,” Peel says. “China remained a major buyer of U.S. pork and increased purchases of beef and broilers as well.”

Total meat production is expected to increase modestly to yet another record level in 2021. “Beef production is projected lower year over year, with pork and broiler production expanding,” he says.

Domestic consumer demand remained remarkably robust through 2020 and may continue in 2021. “However, government actions to provide stimulus in 2020 faltered late in the year and the pressure of the recession may become more apparent going forward,” Peel says.

*Click the image for greater detail

Cattle bouncing back

The USDA Economic Research Service (ERS) forecast improved second-half 2020 beef production due to higher-than-expected fed cattle and cow slaughter — up to 27.1 billion pounds for 2020 (as of mid-October). The ERS also predicted beef production next year will increase slightly due to higher-than-expected fed-cattle marketing.

“The cattle industry has had a pretty significant bounce back,” says Katelyn McCullock, director of the Livestock Marketing Information Center, based in Lakewood, Colo. “The good news is the third quarter will be better than we thought; the fourth, maybe not. We’re still looking at a long road to recovery because the supply chain disruptions affected beef more than poultry and pork.”

The livestock sector is a dynamic throughput system, so if one area shuts down, it affects the others, McCullock notes.

In general, labor shortages were common before COVID-19 because of a tight labor market. “Now, higher turnover will push the industry to further increase automation and robotics so they don’t have to rely on labor,” McCullock says.

On the feedlot side, they had to deal with a supply backlog as cattle were not being slaughtered at the same rate as the past because of labor shortages, plant shutdowns and uncertainty, she says. More cattle meant more feed, so feed orders went up and/or were rationed to control costs and cattle growth.

The cow/calf sector may not have felt the same impact from the pandemic as other livestock segments but still dealt with uncertainty and volatility over prices, where to send calves and concern over drought’s impact on feed prices and availability, McCullock says.

“Whenever the industry undergoes a major event, the crisis lends itself to innovation to solve these problems and refocus,” says McCullock, noting how beef has been re-fabricated and re-routed more heavily to retailers instead of restaurants.

“Consumers are also now experimenting with cuts, recipes and new gadgets for their kitchens,” McCullock says. “The return to home cooking will change the industry for a while.”

In 2021 and 2022, cow prices will likely be higher, as cattle inventory is in a cyclical downturn. “The cow/calf sector will have improved revenues in 2021,” McCullock says.

*Click the image for greater detail

*Click the image for greater detail

Poultry focusing on foodservice

As a result of COVID-19-related plant and labor disruptions, chicken supply will grow just 1.6 percent in 2020, according to predictions from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), relative to the 3.5 percent growth the USDA expected in 2020 prior to the pandemic.

“Higher chicken production will most likely occur again in 2021, albeit the rate of increase will be more modest than the long-run historical rate,” says Tom Super, senior vice president of communications at the National Chicken Council, based in Washington, D.C. “Record output will be achieved, with more birds and an inching-up in heavier average weight per bird.”

When 2020 began, chicken producers were realistically optimistic that they would experience a year of normal, if not above average, favorable returns on their investments and efforts, Super says.

“Even though new plants were ramping up production and a number of existing facilities had expanded their slaughter capacity, increasing domestic and export demand for chicken seemed poised to keep a good balance in the marketplace,” says Super. “USDA at that time saw production for 2020 near the long-run annual pace of 3.5 percent.”

Feed and fuel costs were manageable. China was reopening its market for U.S. poultry after four years of being closed. The U.S. economy was robust, unemployment was low and consumer confidence was high.

“But by the end of the first quarter, as the COVID situation began to more severely impact the economy in many unprecedented ways, the operating and marketing environment for chicken and essentially all aspects of America came under a dramatic change,” Super says.

Chicken slaughter facilities wrestled with staffing their operations in a manner that was safest for workers.

Restaurants changed their formats to offer curbside pickup, more carry-out and deliveries. “Although foodservice demand for chicken is slowly returning to a more normal level, losing this marketing channel that accounts for about 50 percent of overall domestic sales volume required essentially all chicken companies to pivot their go-to-market plans overnight when lockdowns and stay-at-home orders took place,” says Super.

Quick-service restaurant chains where chicken is most popular across the board have been able to focus resources on drive-through, carryout and home delivery.

“A major positive note is that the chicken sandwich war is becoming more intense,” Super says. “Chicken chains that have in the past heavily relied on bone-in/skin-on fried chicken are now not only adding their versions of chicken sandwiches but are trying to one-up the competition by having the best and most tasty offerings.”

Broiler exports should increase modestly in the months and quarters ahead, as has been the situation in 2020 and earlier.

“At the same time, it is fair to note that U.S. animal agriculture is also facing rising feed costs as this year’s crop harvest came in short of earlier expectations and exports of corn and soybeans, especially to China, are adding to demand,” Super says.

According to the USDA, consumption of meat and poultry will total about 225 pounds per person in 2020 and again in 2021, causing hope for a better year ahead for chicken producers.

Pork increasingly in demand

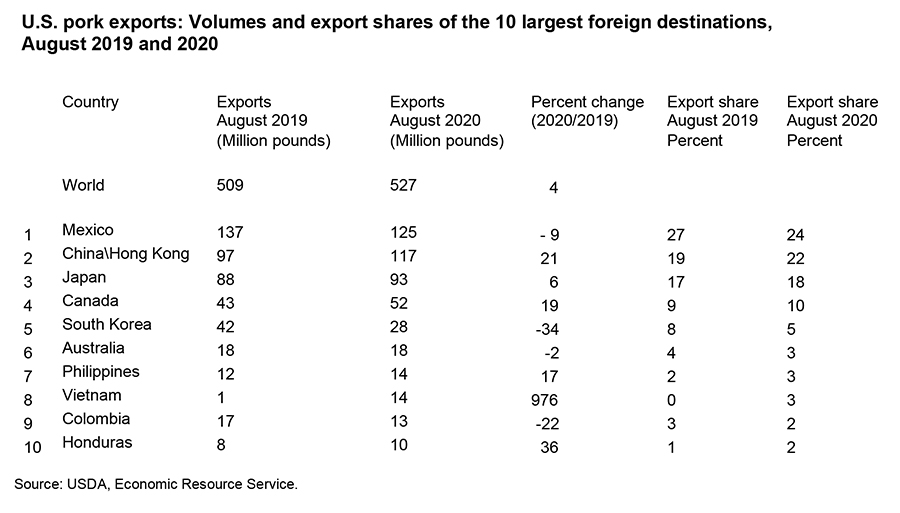

The ERS revised its 2021 pork production forecast to 28.5 billion pounds, an increase of 1.3 percent. While the domestic market shows a slow rebound, exports are anticipated to hold steady at around 7.4 billion pounds because of weak demand from major importing countries.

The year was expected to be good, with lean hog futures suggesting higher prices, increased supplies and gains from trade deals. “The higher prices and supplies suggested a shift in demand — domestic and global,” says Lee Schulz, associate professor at Iowa State University, in Ames. “Then COVID exploded.”

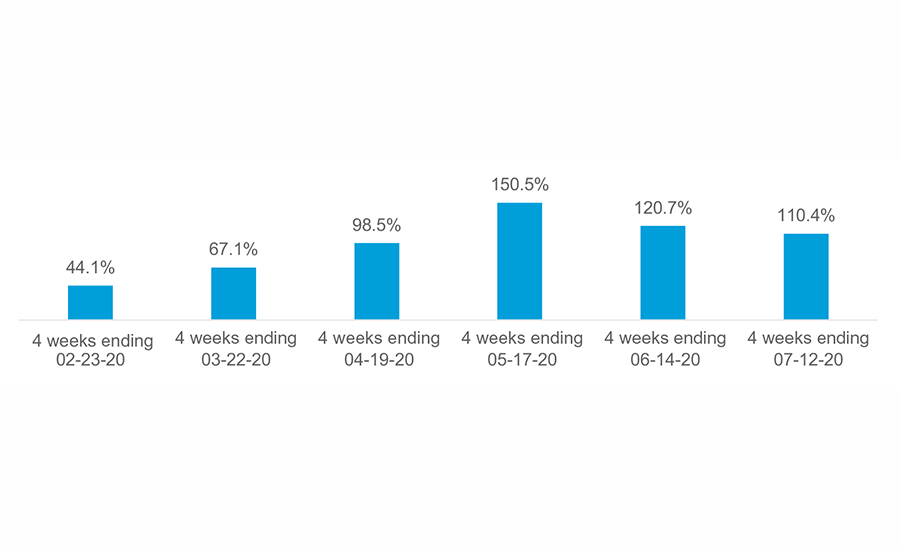

Schulz says the presidential executive orders to keep packing plants open were helpful to maintain the supply chain, particularly in April and May. “We did see product pulled out of cold storage to meet the demand at retail, even if it wasn’t ready for grocery stores with its larger packages and meat cuts meant for export markets,” and prices remained strong, he says.

Packing plants’ limited capacity and restrictions affected where and which proteins could be purchased. Foodservice closures, packing plant shutdowns and hog backlogs all led to eroding profits. “Some producers lost $30, $40 or $50 a head,” Schultz says. “There were significant losses in June and July — besides losses in April and August. Recently we’ve had a run of profits, so the year will average below breakeven profits.”

Although producers tried to slow the growth of hogs with diets because slaughterhouses were closed or backed up, hundreds of thousands of hogs still had to be euthanized in the spring, Meyer says. “For the rest of the year, the industry wasn’t able to operate at full capacity, but they are at 97 percent now, which is much better than I thought,” he says.

While looking into 2021, prices should rebound in the fourth quarter of 2020. “For 2021, lean hog futures suggest prices that are 10 percent to 15 percent higher,” Schulz says.

Domestic consumer demand for pork is higher in 2020 than 2019, notes Meyer, up 2.5 percent in September alone.

Pork exports are doing well, primarily because China is importing U.S. pigs. “There’s still worldwide concern about African swine fever,” says Meyer. “This could be an opportunity for the U.S. to pick up business. China is aggressively trying to rebuild its herd but is two to three years away.”

So, 2021 may very well look a lot like 2019 — same supply, similar prices — which may be surprising.

“In the beginning of the pandemic, a lot was discussed about the inflexibility of the industry (related to pork production), but it has shown resiliency in the face of a once-in-a-lifetime disruption,” Schulz says. “The word ‘unparalleled’ is used a lot, but it’s important to understand how truly historic the disruption we faced from COVID was — and remarkable that we recovered.”

Turkeys filling grocery carts

“It’s been a challenging year, but there are opportunities for turkey with the upcoming holiday season and in 2021,” says Joel Brandenberger, president of the National Turkey Federation, based in Washington, D.C.

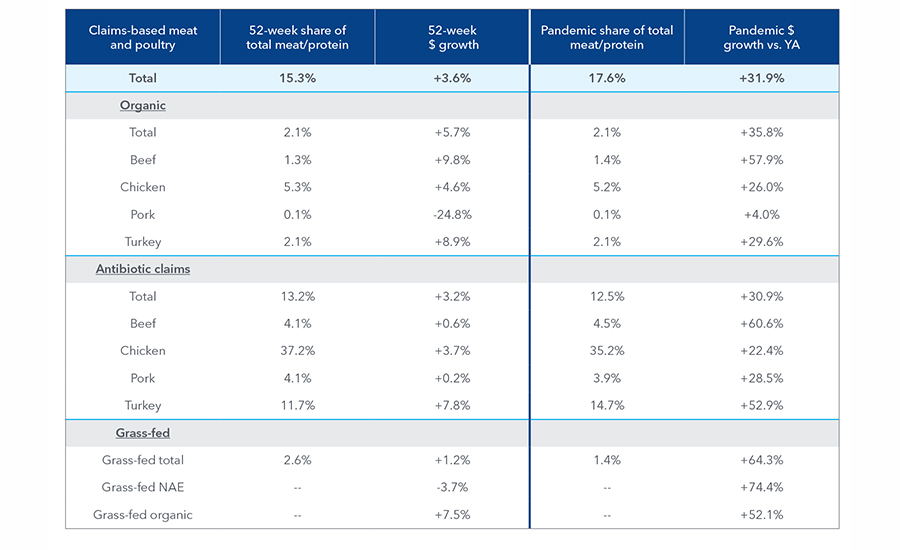

While turkey has come back some at foodservice, it’s not back to where it was. On the flip side, shoppers bought turkey at retail four times more than the previous year, an increase of 19.6 percent or a quarter of a million pounds, according to IRI scanned data for April through September, Brandenberger says.

*Click the image for greater detail

Whole-bird sales are also up 28 percent, to $21 million in sales, and ground turkey sales were up 30 percent.

“I think it’s pretty significant that COVID’s impact at retail was not as bad, although it doesn’t make up for foodservice sales,” says Brandenberger. “There is reason to believe that some consumers made changes in their purchasing habits that will last long after the pandemic has ended.”

The ERS forecasts total turkey production at 5.738 billion pounds, 1 percent lower than 2019. Next year, turkey production is predicted to grow nearly 1 percent to 5.77 billion pounds.

“At this point, the turkey industry has shown elasticity in pricing,” Brandenberger says. “Our sales are still up even with our prices increasing. There is price tolerance for turkey among consumers.”

Brandenberger credits the government and private sector with working well together in a time of crisis to keep the meat supply chain open.

There’s every indication that turkey will still remain center of the plate regardless of whether families can gather or not. “We don’t anticipate a negative impact on the volume of turkey sales for the holidays,” Brandenberger says.

Another bright spot for turkey is exports. “We resumed sales to China before COVID. We’re not back to 2015 levels, but China is our No. 2 export market and Mexico is No. 1. We haven’t seen the pandemic close [export] borders,” he says.

Growing optimism for 2021

Potential changes with a new administration may cause some initial uncertainty next year, which is to be expected.

For 2021, the meat trade does look strong with growing demand in China continuing as the major driver in international trade, Peel says.

“The pandemic continues and is surely a story without an end at this point,” Peel says. “I am cautiously optimistic about meat demand, both domestically and internationally, but there is much uncertainty and potential for additional disruption and pressure in 2021.”

The pandemic will surely continue to be a drag on meat industries, but there may be an opportunity for pent-up demand to burst if the pandemic is controlled, Peel says.

“Structural and behavioral changes may impact meat industries for a long time or permanently,” he says. “It is unknown how much, for example, home consumption may be permanently increased. Will restaurants continue with permanently streamlined menus and more emphasis on take-out and delivery compared to dine-in? Is business travel permanently altered by work from home and Zoom meetings?”

The meat industry learned a lot in 2020 from COVID-19 and other disruptions, which can only be a benefit going forward. During normal times, efficiency is most valued for the supply chain; now we have added more resilience. “The calculus involved in making change is complicated, and we fail to calculate what led us to today, such as economies of scale,” notes Schulz. “Any changes need to be based on sound information.” NP

Report Abusive Comment